Ex-Time reporter: The day I knew journalism had died in America

- truth81

- Aug 7, 2022

- 4 min read

August 7, 2022

By Kenneth R. Timmerman | The New York Post

I have covered war, espionage and intrigue for major news organizations in the United States and around the world, including the New York Times, Newsweek, Time magazine, Reader’s Digest, CBS 60 Minutes, ABC News, Le Monde, L’Express, Le Point, and many others. That was when these organizations still tried to be “mainstream” and did not pull punches, self-censor and lie to protect their political allies.

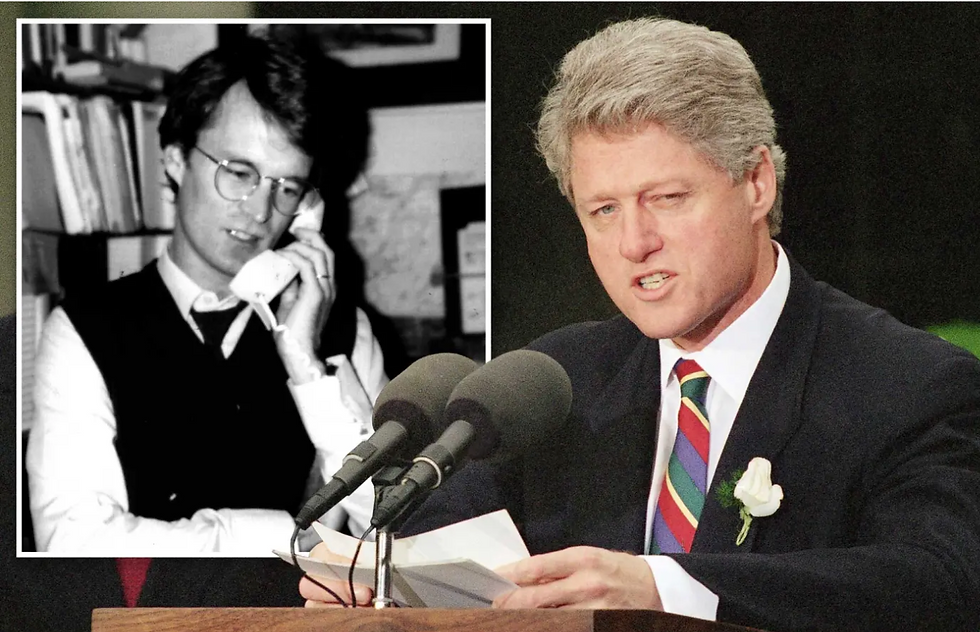

Only when I was fired by Time in 1994 for investigating a story that threatened President Bill Clinton and many senior officials in his administration did I begin to understand that the mainstream media was dead.

The first war I went to cover was the Israeli invasion of Lebanon in 1982. As a Left-Bank expat living in Paris, I naturally sympathized with the Palestinians and planned to embed with a pro-Palestinian NGO in beseiged West Beirut. I wanted to write about the plight of innocent civilians whose lives had been shattered by war.

I wanted to write about the “little” people, not about politics and politicians.

What I eventually learned went far beyond my wildest nightmares. The Palestinians rejected my credentials from their own diplomats in Europe, and threw me in an underground cell as a suspected Israeli spy.

There were 15 of us packed in the cell, which couldn’t have measured more than 16 by 10 feet. There were Lebanese Christians and Palestinians seeking to flee West Beirut, Kurds, Syrians and even a Somali. All of them smoked to hide the kerosene-fringed stench of the latrine bucket and their own clothes, and I smoked with them, but it just made the air thicker and more fetid. For 24 days and nights, we got pounded incessantly by Israeli fighter-jets, naval guns, tanks and artillery. The building had eight floors when I arrived, and was reduced to one and a half floors and pancakes by the time I was released.

One day two American reporters, guests of the PLO, took refuge in the underground shelter during an air raid. A cellmate, a French foreign legionnaire, started whistling the French national anthem and I joined him. Then we whistled the Star Spangled Banner and the two journalists, terrified, turned their backs on us and studiously ignored what they were hearing.

Later, I was taken upstairs for a “bastonnade,” a beating on the soles of the feet using three lengths of metal-shielded electric cable, twisted together and bound with tape. The pain was beyond anything I could imagine, and eventually I passed out.

I certainly learned more about the “little people” as a hostage than I ever could at a press briefing or from some senior official. Speaking directly to the bit players of world history — not the stars — became a habit I have kept to this day.

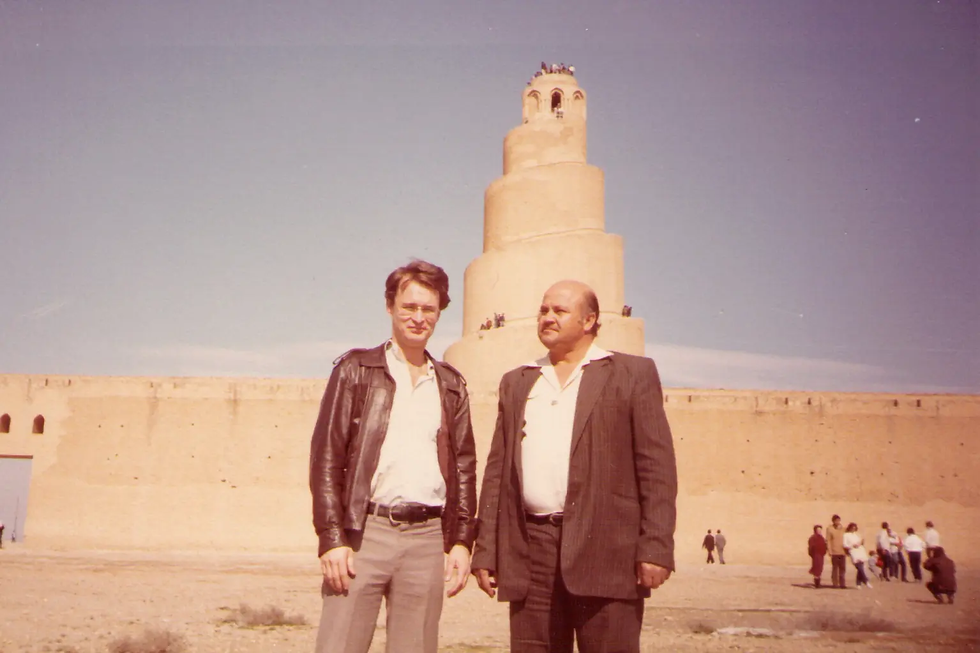

Before the first Gulf War I made many trips to Iraq, where I got to know virtually every Western arms dealer. (Hint: arms dealers love to talk). I also tracked down and interviewed the heads of Iraq’s ballistic missile, nuclear and chemical weapons programs, before anyone even knew their names.

I returned to the States after 18 years overseas to work for Congressional Democrat Tom Lantos as a specialist on weapons of mass destruction, and subsequently joined a new investigative team at Time magazine. Sources in the AFL-CIO Machinists Union tipped me off to strange doings at the B-1 bomber plant in Columbus, Ohio, midnight visits by Chinese intelligence officers, and frustrated US Customs agents. As I investigated, encouraged by Time editors, I uncovered and documented a massive effort by China to buy sensitive military production gear from US weapons plants, seemingly with the benediction — or at least, a blind eye — from Clinton administration officials.

Eventually, along with other reporters, I put together a four-page story on the scheme that was scheduled to run in mid-July 1994. After a Friday lunchtime staff meeting, the Washington, DC, editor, came into my cubicle. “You’ve pissed off people in the administration with your questions,” he said.

“I thought it was my job to ask difficult questions of the administration,” I said.

He fired me on the spot and pulled the story, which ran a year later under the title “China Shops” in the conservative American Spectator magazine. Three years after I was fired, the exporter, McDonnell Douglas, was indicted for export violations, and Sen. Fred Thomson and Rep. Christopher Cox launched massive investigations into the Clinton sell-off of sensitive US technology to Communist China that led to the creation of the US-China Security Commission, which continues to investigate Chinese misdeeds today.

A source at the Commerce Department later showed me the complaint that his predecessor, an assistant secretary, had faxed to the editor-in-chief of Time magazine the day before I was fired. It was explicit, and called for them to pull the story.

Time’s editors showed in July 1994 that they believed their job was not to uncover the truth but to provide political cover to Democrats in Washington. It’s only gotten worse since then, but I believe this incident formally marks the end of the “mainstream media” as we once knew it. Like many other countries in Europe and elsewhere, we now have a politicized media in the United States. But unlike other countries, in all but a few cases our media refuses to acknowledge its ideological affiliation. So added to bias, you have hypocrisy.

Kenneth Timmerman is the author of 12 books of non-fiction and four novels, and was nominated for the Nobel Peace prize in 2006. The piece is adapted from his new memoir, “And the Rest is History: Tales of Hostages, Arms Dealers, Dirty Tricks, and Spies,” (Post Hill Press), which will be released on August 30.

![🎥 Francis R. Connolly: “From JFK To 911 Everything Is A Rich Man’s Trick” [FULL DOCUMENTARY]](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/d3caba_7a62d6fe51c64c778ceb96b3aad45ca9~mv2.png/v1/fill/w_960,h_580,al_c,q_90,enc_avif,quality_auto/d3caba_7a62d6fe51c64c778ceb96b3aad45ca9~mv2.png)

Comments